By Ian Mitchell

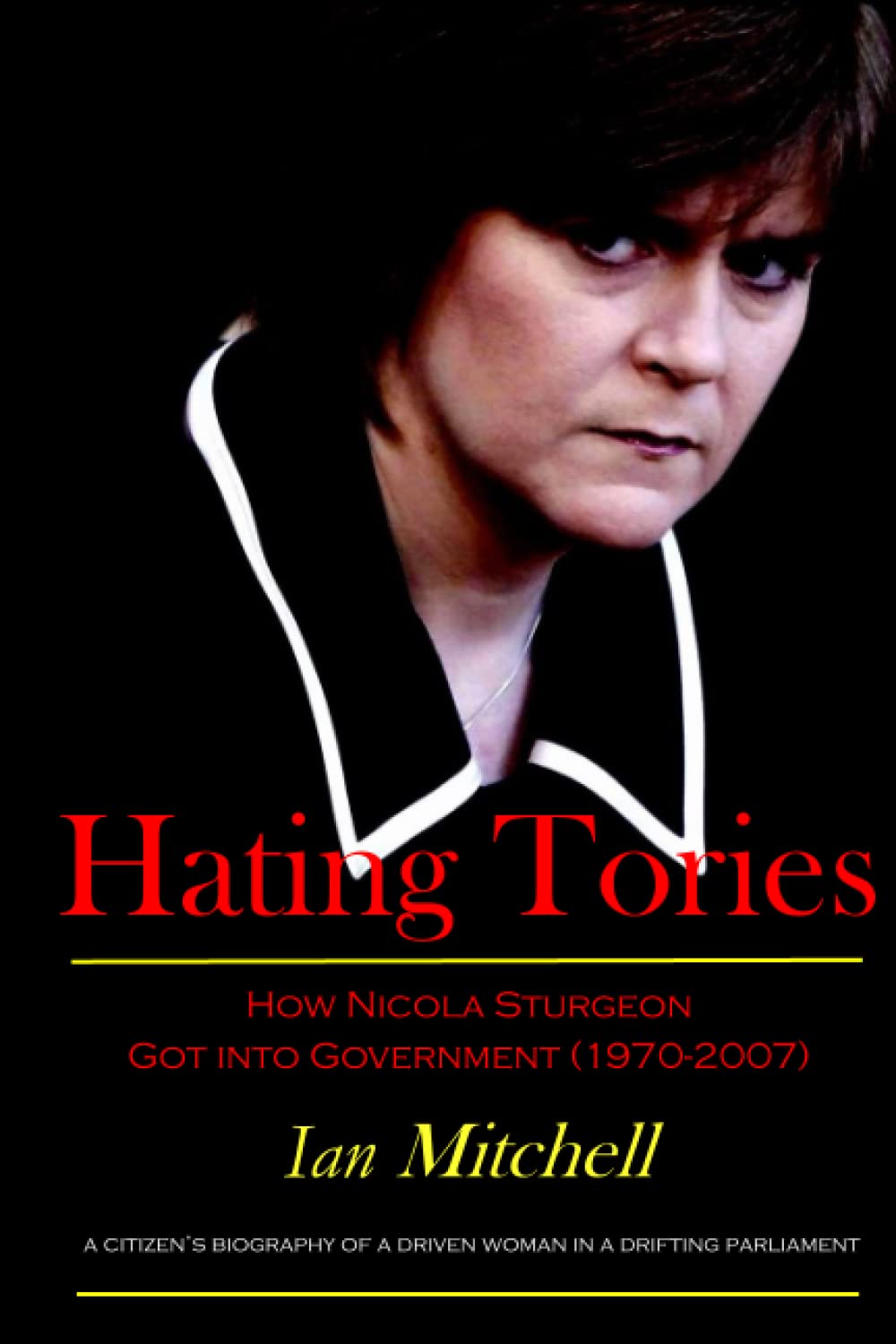

I have written a book which I have called “Hating Tories” as it is about the parliamentary career of Nicola Sturgeon and I am convinced that hatred and negativity are the defining characteristics of her political outlook. The subtitle of the book is “How Nicola Sturgeon Got into Government (1970-2007)”. The title might give the impression that I have a rooted prejudice against Sturgeon and the SNP. I do not. In fact, I voted SNP for thirty years, before I went to Moscow. After twelve years in Russia I returned to Scotland convinced that there were far too many parallels for comfort between the regime in the Kremlin and that in Bute House.

But who am I to say such things? I am merely a citizen who happens to be Scottish but who, like any other citizen, has also has had certain experiences (including spending many years as a youth in apartheid South Africa) which have shaped my views about life in general, and more recently about Nicola Sturgeon in particular. They will doubtless not find favour with the First Minister herself, but that is why I have written my book. If I have one fundamental belief that all my experiences as a citizen have convinced me of, it is that the only hope for civilisation is the spread of the rule of law.

The rule of law is a much-used expression which is also much misunderstood. I have written about it at length in my previous book: The Justice Factory: Can the Rule of Law Survive in 20th Century Scotland? It is a complex (and fascinating subject) but at its simplest, it is about a society in which those who make the rules are chosen by those who have to obey them. That involves an element of reciprocity in the relationship between the rulers and the ruled, which means information flows up to our masters as well as down from them to us peasants.

Democracy is one way of conveying upward to government the opinions of those at the bottom of the political heap. Now if there is one thing which most clearly marks out the Sturgeon regime—and the Putin one in Russia—it is the unwillingness to listen to those who are not within the magic circle of those with power and perks. As I see Scottish politics today, it is a conspiracy between parliamentarians and the civil service in a loose group which I refer to in Hating Tories as “the bureaugarchy”. Putin has his oligarchy; Scotland having a more bureaucratic outlook, prefers a bureaugarchy.

The clearest case of rule by unaccountable committee is, of course, the European Union, and it is no accident that Sturgeon’s main aim in political life, after detaching Scotland from Westminster democracy, is to transfer it to the empire of office-wallahs and their confidential memos and expensive dinners in Brussels.

If there is one characteristic of civil service hierarchies which is almost universal, it is that they do not want to hear the views of those their policies affect. That has always been the case. They are the sacred guardians of holy power and demand respect on that point, without argument or comment. This paper-based elitism began in the Catholic Church after the Gregorian reforms in the 1070s. The Reformation attempted to break the power of clerical bureaucracy in Europe, just as Brexit tried to break the power of bureaugarchy in Brussels more recently. Nothing unusual in either development.

What is new is that we have a government in Scotland which prefers bureaugarchy to democracy since that allows Bute House to govern Scotland without any significant public involvement. The big smells in St Andrews House know that those who vote for “My Leader Right or Wrong” are in fact shirking their democratic responsibility to give due thought to the government-opposition choice before casting their vote. That suits them just fine, which is why they do nothing to halt that trend. Indeed, in many ways, they seem to encourage it.

Broadly speaking, leaders with unshakeable positions with weak or frightened opposition, like Putin in Russia and Sturgeon in Scotland, use their power in one of two ways: either they work for the country, or they work for themselves. Wealthy “aristocrats” tend to make the best politicians as they do not need to steal. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was an example of that sort, as was Lord Salisbury at the end of the nineteenth century and, more arguably, Lord Grey, who piloted the first electoral Reform Act through parliament in 1832.

That is not to say that everything such statemen do is right, far from it. They make mistakes, like everyone else, but they tend to take decisions on public policy without considering what they might get out of them personally. Such men did not need to dip their hands in the till, so public life acquired a reputation for general honesty and tolerable efficiency. That is not true today.

Both Westminster and Holyrood are corrupt to a degree, and the fact that we have a millionaire Prime Minister does not make as much difference as it should. But there is a difference between Westminster corruption and Holyrood corruption. In England, corrupt politicians favour their friends in all sorts of inappropriate ways. Some get rich as a result of these favours. Others are offered jobs they might not otherwise have been able to get. It is a cursed circle of people who help each other—bad karma all round!

Corruption in Scottish power circles operates differently, and the reason is the nature of Nationalism. In a post-colonial world nationalism is almost always petty, local and negative, as Vladimir Putin so well illustrates. The same is true in Scotland. The idea of transferring the country from a semi-democratic state to a bureaucratic regime in Europe is itself petty, localistic and negative. But it is of a piece with Nicola Sturgeon’s entire political philosophy. It is based less on helping your friends, as the bad apples in Westminster do, than on trying to destroy your enemies, which is what almost all the apparatchiks in the SNP desks at Holyrood are set on doing.

The only exception I have noticed is Ash Regan, the bright-looking redhead who would simply not thole the Gender Recognition Reform Bill and resigned from the government. I would not be surprised if she were given the Alexey Navalny treatment in another form in an effort to destroy not just her powerbase within the SNP, but also her career, life and personal happiness. Destruction of competing power bases is what most politics is all about, and to an extent is “fair play in parliament”.

But to extend that to the wokish extreme of attacking the private life of public enemies, is to head down into the gutters that Putin and his friend Belarus, Alexander Lukashenko, seem to enjoy inhabiting. This is common today amongst the international saddo community, but it is relatively new to politics in Britain. It has been the basis of the Nationalist approach to power. That is what my research into the origins of Nicola Sturgeon’s political personality has shown. It is precisely her approach to enemies. They are not to be beaten but destroyed.

Think of the campaign against Rangers Football Club, for example. Apart from the failed farce of the Offensive Behaviour at Football Act (analysed in some detail in The Justice Factory – part II section 4(b), p. 358ff), there was the persecution of the owners of the club, which has, so far, resulted in nearly £60 million of public money being paid to compensate them for the attempt to destroy their lives.

Likewise, the Named Person scheme sprang from an attempt to destroy the ordinary confidentiality of family relationships. The Hate Crime Act is equally destructive of private trust within families. Sturgeon says endlessly that she thinks private life should be separated from public life, and I agree entirely. However, she proceeds to use the power of the state to attack individual in the citadel of their own sitting rooms.

The gender reform Bill is of a piece with all of that. However, human nature not being like angry-nationalist nature, the Scottish people appear to have at least decided that enough of this political bullying is enough. Sturgeon has destroyed the unity of her own party by her refusal to listen to warnings of trouble ahead. In an independent Scotland, I would not be surprised if she would want to legislate to prevent anyone else taking power. But luckily we are still part of the United Kingdom, where elections are conducted in a broadly honest manner and so reciprocity can emerge from the ashes of any personality cult. Any attempt to pervert the constitution, like Putin’s lifetime in office, would be thrown out by the UK Supreme Court.

A small part of the campaign to enforce reciprocity is my own book. I am expressing the view of a citizen on facts which are undeniable as they are culled almost exclusively from the Official Report of the proceedings in the Holyrood parliament. It is an extremely important and user-friendly resource, and the parliamentary information office, which supervises its production, is one of the few departments of the Scottish civil service which is not polluted with nastiness, partisanship or arrogance—and in some cases, extraordinary stupidity (see The Justice Factory, p. 385-6 for the Scottish Government’s Tourism and Major Events Division’s attempt to reinterpret St Andrew’s role in the Bible from being a “fisher of men” to one who ran courses on fishing technique for locals in the Galilee area).

I do not care a hoot if those citizens of Scotland who sit in the parliament think I have not done full justice to the saintliness of their behaviour and the ethereal wisdom of the words they have spoken in the chamber. As a Scot, I claim the right to speak my mind on public issues without fear or favour, and to comment on the behaviour of all those who seek power over us. I try at all times to be fair, but not to be “objective”, as that is impossible outside the measurable sciences. I have a particular point of view, and readers of my book will be in no doubt about that by the time they reach the end, and therefore able to make up their own minds about the justice or otherwise of my claims, observations and judgements.

I also have a side-kick, Hamish Gobson, who lives on the isle of Great Todday and commentates from an even more teuchterish point of view than I do. He occasionally writes for public consumption, as for example, recently in a comment about the gender debate. But his main value is as a person who treats all politicians as deeply suspect simply because they try to seek power over others in peacetime. His interventions in my text are both welcome and amusing—though I doubt Ms Sturgeon would get the joke, or indeed any other joke: too wrapped up in her own saintliness.

Ian Mitchell is the author of several books about Scotland, the most recent of which is Hating Tories: How Nicola Sturgeon Got into Government (1970-2007). It was published last week and has been called by Prof. Tom Gallagher “This is a pithy and well-researched study of Scotland’s ill-starred devolution experiment and the figure who has acquired more power in her domain than any other person in British history for a long time.”

Leave a Reply